My brother had a dog that used to sing along with the chorus:

Here at the frontier, the leaves fall like rain. Although my neighbors are all barbarians, and you, you are a thousand miles away, there are still two cups at my table.

Ten thousand flowers in spring, the moon in autumn, a cool breeze in summer, snow in winter. If your mind isn't clouded by unnecessary things, this is the best season of your life.

~ Wu-men ~

Friday, October 31, 2014

Tuesday, October 28, 2014

Zhang Zhuang in Taijiquan

Anyone who has known me or has read this blog for the last 9 years knows that zhan zhuang, the standing stake practice, has had a big impact on me.

Below is an excerpt from a post by Jim Roach at the Classical Tai Chi Blog. The full post may be read here.

Below is an excerpt from a post by Jim Roach at the Classical Tai Chi Blog. The full post may be read here.

Zhan Zhuang for Taijiquan Practice. The Wuji Positions allows the

practitioner to relax the mind, while, adjusting, aligning, and balancing the

body to produce correct postures. Zhan Zhuang Training, on the other hand,

strengthens the tendons and ligaments, aids in balancing, teaches the muscles

to relax, and identifies weaknesses not noticed while practicing the Form. This

is important in helping to identify the proper placement of the heel and

weighting of the empty foot.

The Square Form of Classical Taijiquan, brush knee movement is being used to illustrate how

Wuji and Zhan Zhuang can be applied at

those stopping points for each position. Applying these training methods in

addition to form practice will help the student in developing strength and

proper form. Wuji is defined as nothingness, the beginning before intention and

movement. Wuji is discussed in many Taijiquan Books written by both

practitioners and masters alike. These writers mainly address Wuji in the

Preparation Posture and/or the Closing Posture of the Taiji Form. As such,

most readers are left to believe Wuji is only accomplished at the beginning and

ending of the Taiji Form. However, this is not so. Wuji is practiced during

every posture, that is, every posture begins with Wuji, moves into Taiji, and

returns to Wuji.

Zhan Zhuang (standing like a stake, standing like a tree) Training is a way to relax both

the nervous and muscular systems simultaneously. This is accomplished by

combining exertion and relaxation simultaneously. Breathing is done by inhaling

and exhaling gently through the nose while keeping the mouth closed and

relaxed. The chest, stomach, and hips are in a relaxed state. Zhan Zhuang helps

with the identification of the energy flow in the different positions and

trains to keep the localized nerve activity dormant (Forum 6); as well as,

strengthening the yin side of the posture for strong rooting and building power

(Forum 7). There is no set time limit in Zhan Zhuang Training; however, the

seasoned practitioner has been known to hold the positions in excess of twenty

minutes. Some have claimed to be able to hold the positions for hours. It is important

to remember, that as the tension builds in different parts of the body, to tell

yourself to relax. (RELAX, RELAX, RELAX) Start with short time frames and

increase the holding time slowly.

Saturday, October 25, 2014

Recent Works by the Warrior Poet, Cameron Conaway

Cameron Conaway, the author of Caged: Memoirs of a Cage Fighting Poet, was nice enough to write this guest post for Cook Ding's Kitchen, describing what he's been up to since he hung up his gloves. Click on the "Warrior Poet" tag for Cameron's other posts for Cook Ding's Kitchen. Enjoy.

Picking Shots

Exclusive to Cook

Ding’s Kitchen

10/18/2014

It was June 2007 at the Erie

County Fairgrounds in Sandusky, Ohio. It was also Ohio Bike Week. A field of grass, revving

engines, a blazing white sun bursting through blue skies, beards and beer and

cheering and high heels and leather jackets and a steel cage in the middle of

it all. This was Ohio; this was ancient Greece. This was the most terrifying

moment of my life but, as was always the case, when the steel cage shut and the

referee said, “Let’s do this” and disappeared until the end it was... Zen. Life

or death. It was a sport but in no way felt like one. Absolute survival.

Absolutely serenity. Peace and violence swirled like the skies in Van Gogh’s

Starry Night. There were no thoughts; instinct guided action. I hurt and I

got hurt. I survived knowing that a bell, a mindfulness bell, would bring me

back to the beginning or the end. Whatever they are. I just wanted to be the

greatest fighter on the planet.

I lost that fight. Ate a knee that kissed my organs. Pulled

guard and felt the back of my head bounce off the mat. Found myself in a heel

hook I didn’t know how to escape. Tapped the mat three times to signal defeat. Other fights to fight, I told myself.

Whatever that means.

Two months later I’m walking through the University of Arizona’s Poetry Center

trying to find how in the hell poetry could be wielded. It had to be wielded.

All I knew was wielding. So it had to be wielded for good. What’s the point of imagination? I wondered as I looked at these

beautiful little books. Why is it often

linked to escaping reality? Shouldn’t it be linked to better understanding

reality so that we can beat the shit out of the world’s problems? I haven’t

fought since 2007 but it’s all I think about. Who knew poetry is just as much

about the scrap.

Poetry book one, Until

You Make the Shore, was based on the absurdities I saw in an Arizona

juvenile detention center and the US criminal justice system in general. Can

poetry solve that? Hell no. But Allen

Ginsberg said, “The only thing that can save the world is the reclaiming of

the awareness of the world. That’s what poetry does.” If there’s a tenet I live

by or if I have a faith it probably begins somewhere near that. I’m just a simple

dude trying to do some social good with whatever skills I have and whatever

time I have left to use them. I don’t see a better point in being here.

Book two, Malaria,

Poems. The disease ravages nearly a million human beings each year. Us and

them are illusions. There is only we. So why in the sweet holy hell is nobody

talking about malaria? And why is so much of our “global health” money going

toward causes like male pattern baldness? Enter a pissed off version of Ginsberg’s

voice.

Book three, Chittagong:

Poems & Essays, is primarily about the horrors of the shipbreaking

yards I saw in Bangladesh. Again it was all about what do I have and what can I

do about the madness before me? Boys are getting crippled and dying from

exposure to toxins all to break down the cruise ships we the wealthy love to

lounge on. And it’s only crickets? Stage left: Ginsberg’s ghost is now

screaming the quote while interspersing F bombs.

I’d like to think that if Ginsberg were my age he’d want to

grab a craft brew or two and talk about this shit. Who knows. But I know a lot

of others who do and will and want to. I feel the world’s torn—that muddled

place where it can swim but its toes don’t touch—between social consciousness

waxing and waning, at once breaking through the surface of the mud and

blossoming like the lotus and unable to break the surface of the mud and simply

suffocating. I just want bloom, sustainable and brilliant bloom.

I don’t know what’s next; but I’m covering up and backing up

towards the corner of desperation and my chin is tucked and I’m ready to swing

when there’s an opening.

Tuesday, October 21, 2014

Dao De Jing #53: Difficult Paths

I find it a little ironic that this selection, Difficult Paths, came up right after the half marathon.

The Dao De Jing is not only one of the world's great classics, it is one of the foundations of Philosophical Daoism. A free online version of the Dao De Jing may be found here. Below is verse#53, Difficult Paths

53. Difficult Paths

With but a small understandingOne may follow the Way like a main road,

Fearing only to leave it;

Following a main road is easy,

Yet people delight in difficult paths.

When palaces are kept up

Fields are left to weeds

And granaries empty;

Wearing fine clothes,

Bearing sharp swords,

Glutting with food and drink,

Hoarding wealth and possessions -

These are the ways of theft,

And far from the Way.

Sunday, October 19, 2014

Thursday, October 16, 2014

Birthday Post

Today is my birthday. Won't you help me to celebrate?

Months pass,

days pile up, like one intoxicated dream -

An old man sighs.

- Ryokan

[from 'One Robe, One Bowl', translated by John Stevens]

When I began the new job about a year ago I also began working from home. Sure I had to travel, but when I was home I was completely home and I liked that a lot.

Ironically, I also found that I began to feel a need to get out of the house! I also started to put some weight on from the traveling and noticed that some of my good habits were eroding.

I started kicking around the idea of getting out the house by beginning training in aikido again, and/or perhaps judo.

I found two dojo located fairly nearby. The first one only trained on Saturday afternoons, which is absolutely the worst time for me; plus what they worked on was sort of a mash up of what the teacher put together of aikido and judo.

The second seemed ideal on paper. Aikido followed by judo (or vice versa, I can't remember), twice a week on Tuesdays and Thursdays. Unfortunately they wouldn't return emails or phone calls. It seems that they have closed.

While I was kicking around my options, the Mrs reminded me that a friend of hers has been going to an MMA gym for years, has a great time and is always talking about what a great bunch they are there. I decided to attend the free conditioning class and see what it was about.

I immediately signed up. I thought that I was in decent shape before but found out rapidly that I was mistaken.

The general schedule is a conditioning class Mondays through Thursdays at 7, followed by kick boxing at 8. On Tuesdays and Wednesdays, they also have Brazilian Jiujitsu from 6 until 8, overlapping the condiitoning class.

I am certainly the oldest guy there. My wife's friend is a year or so younger than I am and her sister is a year or two younger still. There are a handful of guys in their 30's or 40's who show up, but almost everyone is in their 20's including a handful of young women.

The young guys are pretty good to me. They tend to hold back enough to where I'm not getting my block knocked off, but I found that there is a wide range of interpretation of the instructions to "take it easy on the old guy."

In fact, a few weeks into it, I picked up my first black eye.

I simply can't keep up with the gap between my reaction time and those of they young guys. I also noticed that my knees were chronically sore from the kickboxing too.

One of the assistant instructors suggested that I take up BJJ sooner rather than later, which I was planning on. He said that it would be easier on my body and that a lot of my disadvantages would be somewhat mitigated. In fact, having some patience would probably be to my advantage.

Then I saw this clip.

A 74 year old black belt in Brazilian Jiujitsu.

I don't know if this old bag of bones will stay together long enough to achieve that, but it is certainly a worthy goal. As a rule of thumb, it takes a "regular" young person about 10 years to get to black belt level in BJJ, so maybe it will take me 20.

Besides being older, I travel for work and I have other responsibilities that simply doesn't allow me to put the time in that I would have as a young man. It's on the edge of the realm of possibility. You have to be somewhere and you have to be doing something. Why not? I'm game. A realistic shorter term goal is to still be doing this when I'm 60.

I've had a couple of pulled muscles and BJJ is a whole new kind of sore, but it's been six months now and I've stuck with it. I'm still among the least of the grapplers, but I do improve every day and have a blast, which is what it is all about.

One of my regular training partners has developed type 1 diabetes. She's trying to raise money for a Diabetes Alert Dog, which can sense when her chemistry changes and indeed save her life. A type 1 diabetic can slide into a coma while sleeping and simply die. The dog would sense the change and wake her.

I don't want her to die. Maybe you can help her.

I'm 57 years old and I'm not a runner. I haven't run since I was a teenager and 5 miles was the longest I ever ran back then. I have found that running leaves me with sore ankles and knees. It's uncomfortable for me. I'd rather do just about anything than run.

Every dollar counts. Won't you please donate? You'll change, maybe save someones' life. My goal is to raise $1300.

Won't you sponsor me?

Between running and BJJ, I think that NOW I'm in pretty decent shape. I guess that I'll find out in a few days.

I've been at the new job a year now. Both the company and I are pretty happy with each other. I've advanced the relationships they already had from first discussions to several development programs which should see production ramping up either later this year or early next. I've found them some some new customers which whom they've had no contact before.

The travel seems to be pretty seasonal. From autumn to spring is the traveling season. As my boss is in Chicago, I expected to go there quite a bit. As it turns out I've gone to San Diego more times than anywhere else. Not a bad place to visit.

There is a local charitable organization named Life Remodeled. They raise money, organize volunteers and go into areas that need a lot of work and get it done. The last several years they have concentrated on the City of Detroit, which needs a lot of work.

This summer they organized 10,000 volunteers over a week's time to renovate my old high school, Cody High in Detroit, and 100 surrounding blocks in the neighborhood.

That was my neigborhood. I grew up there. I know those houses. I played in those yards. My childhood home is within those 100 blocks.

Between conference calls and what not, I wasn't able to get down there to help and I was quite disappointed. However, even without me, by all accounts everything turned out great.

This month, my wife and I will be celebrating our 31st wedding anniversary.

Time flies like an arrow.

My oldest daughter finished a master's degree and is advancing her career. My youngest daughter completed her college degree and is working in her field. Everyone is doing well.

Months pass,

days pile up, like one intoxicated dream -

An old man sighs.

- Ryokan

[from 'One Robe, One Bowl', translated by John Stevens]

When I began the new job about a year ago I also began working from home. Sure I had to travel, but when I was home I was completely home and I liked that a lot.

Ironically, I also found that I began to feel a need to get out of the house! I also started to put some weight on from the traveling and noticed that some of my good habits were eroding.

I started kicking around the idea of getting out the house by beginning training in aikido again, and/or perhaps judo.

I found two dojo located fairly nearby. The first one only trained on Saturday afternoons, which is absolutely the worst time for me; plus what they worked on was sort of a mash up of what the teacher put together of aikido and judo.

The second seemed ideal on paper. Aikido followed by judo (or vice versa, I can't remember), twice a week on Tuesdays and Thursdays. Unfortunately they wouldn't return emails or phone calls. It seems that they have closed.

While I was kicking around my options, the Mrs reminded me that a friend of hers has been going to an MMA gym for years, has a great time and is always talking about what a great bunch they are there. I decided to attend the free conditioning class and see what it was about.

I immediately signed up. I thought that I was in decent shape before but found out rapidly that I was mistaken.

The general schedule is a conditioning class Mondays through Thursdays at 7, followed by kick boxing at 8. On Tuesdays and Wednesdays, they also have Brazilian Jiujitsu from 6 until 8, overlapping the condiitoning class.

I am certainly the oldest guy there. My wife's friend is a year or so younger than I am and her sister is a year or two younger still. There are a handful of guys in their 30's or 40's who show up, but almost everyone is in their 20's including a handful of young women.

The young guys are pretty good to me. They tend to hold back enough to where I'm not getting my block knocked off, but I found that there is a wide range of interpretation of the instructions to "take it easy on the old guy."

In fact, a few weeks into it, I picked up my first black eye.

I simply can't keep up with the gap between my reaction time and those of they young guys. I also noticed that my knees were chronically sore from the kickboxing too.

One of the assistant instructors suggested that I take up BJJ sooner rather than later, which I was planning on. He said that it would be easier on my body and that a lot of my disadvantages would be somewhat mitigated. In fact, having some patience would probably be to my advantage.

Then I saw this clip.

A 74 year old black belt in Brazilian Jiujitsu.

I don't know if this old bag of bones will stay together long enough to achieve that, but it is certainly a worthy goal. As a rule of thumb, it takes a "regular" young person about 10 years to get to black belt level in BJJ, so maybe it will take me 20.

Besides being older, I travel for work and I have other responsibilities that simply doesn't allow me to put the time in that I would have as a young man. It's on the edge of the realm of possibility. You have to be somewhere and you have to be doing something. Why not? I'm game. A realistic shorter term goal is to still be doing this when I'm 60.

I've had a couple of pulled muscles and BJJ is a whole new kind of sore, but it's been six months now and I've stuck with it. I'm still among the least of the grapplers, but I do improve every day and have a blast, which is what it is all about.

One of my regular training partners has developed type 1 diabetes. She's trying to raise money for a Diabetes Alert Dog, which can sense when her chemistry changes and indeed save her life. A type 1 diabetic can slide into a coma while sleeping and simply die. The dog would sense the change and wake her.

I don't want her to die. Maybe you can help her.

I'm 57 years old and I'm not a runner. I haven't run since I was a teenager and 5 miles was the longest I ever ran back then. I have found that running leaves me with sore ankles and knees. It's uncomfortable for me. I'd rather do just about anything than run.

A

few months ago I found out that nearly 800 million people don't have

access to to clean drinking water. They drink out of mud holes, out of

water holes shared with animals; from wells that are so distant that the

women and girls going to fetch the water are subject to assault,

abduction and worse.

I

live near the Great Lakes and can go out to the middle of Lake Huron

and be surrounded by fresh water as far as the eye can see. To lack

water is a concept that is kind of hard for me to wrap my head around

As

I said, I learned that so many people are living in such desperate

conditions and I also found out that a group named Team World Vision is

raising money to address this.

For $50 a person can have clean drinking water for life.

By running.

And so I run.

This

57 year old non runner has signed up for the International Half

Marathon to take place during the Free Press Marathon on October 19th. I

am taking part in a fund raiser organized by Team World Vision. TWV

distrbutes personal filter straws, builds filtration systems, digs

wells, etc.

I

showed up at the informational meeting held after the service at

church, expecting to simply lend support to one of my daughters who had

been talking about signing up for a marathon. The next thing I knew, I

was filling out a form and was one of the first to hand

it in.

Won't you sponsor me?

Between running and BJJ, I think that NOW I'm in pretty decent shape. I guess that I'll find out in a few days.

I've been at the new job a year now. Both the company and I are pretty happy with each other. I've advanced the relationships they already had from first discussions to several development programs which should see production ramping up either later this year or early next. I've found them some some new customers which whom they've had no contact before.

The travel seems to be pretty seasonal. From autumn to spring is the traveling season. As my boss is in Chicago, I expected to go there quite a bit. As it turns out I've gone to San Diego more times than anywhere else. Not a bad place to visit.

There is a local charitable organization named Life Remodeled. They raise money, organize volunteers and go into areas that need a lot of work and get it done. The last several years they have concentrated on the City of Detroit, which needs a lot of work.

This summer they organized 10,000 volunteers over a week's time to renovate my old high school, Cody High in Detroit, and 100 surrounding blocks in the neighborhood.

That was my neigborhood. I grew up there. I know those houses. I played in those yards. My childhood home is within those 100 blocks.

Between conference calls and what not, I wasn't able to get down there to help and I was quite disappointed. However, even without me, by all accounts everything turned out great.

This month, my wife and I will be celebrating our 31st wedding anniversary.

Time flies like an arrow.

My oldest daughter finished a master's degree and is advancing her career. My youngest daughter completed her college degree and is working in her field. Everyone is doing well.

Monday, October 13, 2014

Free Copies of Research of Martial Arts

Jonathan Bluestein is giving away some free copies of Research of Martial Arts at GoodReads.

Click here for your chance to get one!

Click here for your chance to get one!

Introductory History of Xingyiquan

At EJMAS (Electronic Journal of Martial Arts and Science), noted MA author Brian Kennedy published an introductory history of Xingyiquan training manuals. An excerpt is below. The full article may be read here.

By Brian Kennedy

Copyright © EJMAS 2001. All rights reserved.

A note on transliterations: Although this article uses pinyin to transliterate technical terms, personal names are presented using the spelling by which the person is (was) best known in English. Book titles are likewise presented as on their covers.

The senior students looked anxiously around the table

at each other. Not only had the Master been murdered but the secret training

manual had been stolen. That manual, which had been passed down from master

to senior disciple for over 500 years, contained the key ideas that gave

the school’s techniques their frightening efficacy. The manual had to be

found and the master’s murder avenged, no matter what the cost.

"Secret training manuals" are a stock motif in Chinese martial arts movies

and novels. Unlike other stock motifs such as magic swords and flying through

the air, "secret training manuals" do have a basis in reality and have

a long history in some Chinese martial arts systems.

Training manuals are books or manuscripts that teach the principles,

techniques or forms of a system, and as such are separate from books that

discuss the history of martial arts or works of fiction. Xing-yi quan is

one art where training manuals have existed for several hundred years,

and that history is the focus of this article.

Xing-yi Quan

Xing-yi quan means "form-mind boxing," and is romanized as xing-yi (pinyin), hsing-i (Wade-Giles), and hsing-yi (Yang Jun-ming’s transliteration). Stylistically, it is one of the three internal Chinese martial arts, the other two being bagua (pa kua) and taiji (t’ai chi). Structurally, it is characterized by its seeming simplicity: the system consists of a limited number of forms and techniques that are drilled in series of short forms. However, whatever the system lacks in variety, it makes up for in depth, requiring the student to make a long and intensive study of the basic motions of combat. It is also undeniably practical, having been the system of choice during the late Qing and Republican periods for people such as convoy escorts and bodyguards who made their living fighting.

Xing-yi has two major subdivisions, the Hebei-Shanxi tradition and the Henan tradition. The Hebei-Shanxi schools are much more prominent both in China and in the West. Their core training consist of the 5 element fists and the 12 animals forms. Meanwhile, the Henan schools, although far less prominent, probably represent a more accurate/faithful version of early hsing-i. Their core training consist of 10 Animal forms that are different from the 12 Animal forms of the Hebei-Shanxi lineage.

The Henan branch is also known as Muslim xing-yi. The reason is that the historical founder of xing-yi, Ji Ji Ke, had two major students, who in turn founded the Hebei-Shanxi branch and the Henan branch. The Henan branch founder, Ma Xueli (1714-1790), was Muslim, as were his family and all his students. Since the Henan branch of xing-yi tended to stay within the Islamic community, it subsequently became identified as a Chinese Muslim ("Hui") martial art.

At any rate, the development of modern xing-yi is attributed to Ji Ji Ke, circa 1750, and the subsequent history of its training manuals can be usefully divided into four periods: the legendary period, the hand-copies period, the Republican period, and the modern period.

An Introductory History of Xing-yi Training Manuals

A note on transliterations: Although this article uses pinyin to transliterate technical terms, personal names are presented using the spelling by which the person is (was) best known in English. Book titles are likewise presented as on their covers.

Xing-yi quan means "form-mind boxing," and is romanized as xing-yi (pinyin), hsing-i (Wade-Giles), and hsing-yi (Yang Jun-ming’s transliteration). Stylistically, it is one of the three internal Chinese martial arts, the other two being bagua (pa kua) and taiji (t’ai chi). Structurally, it is characterized by its seeming simplicity: the system consists of a limited number of forms and techniques that are drilled in series of short forms. However, whatever the system lacks in variety, it makes up for in depth, requiring the student to make a long and intensive study of the basic motions of combat. It is also undeniably practical, having been the system of choice during the late Qing and Republican periods for people such as convoy escorts and bodyguards who made their living fighting.

Xing-yi has two major subdivisions, the Hebei-Shanxi tradition and the Henan tradition. The Hebei-Shanxi schools are much more prominent both in China and in the West. Their core training consist of the 5 element fists and the 12 animals forms. Meanwhile, the Henan schools, although far less prominent, probably represent a more accurate/faithful version of early hsing-i. Their core training consist of 10 Animal forms that are different from the 12 Animal forms of the Hebei-Shanxi lineage.

The Henan branch is also known as Muslim xing-yi. The reason is that the historical founder of xing-yi, Ji Ji Ke, had two major students, who in turn founded the Hebei-Shanxi branch and the Henan branch. The Henan branch founder, Ma Xueli (1714-1790), was Muslim, as were his family and all his students. Since the Henan branch of xing-yi tended to stay within the Islamic community, it subsequently became identified as a Chinese Muslim ("Hui") martial art.

At any rate, the development of modern xing-yi is attributed to Ji Ji Ke, circa 1750, and the subsequent history of its training manuals can be usefully divided into four periods: the legendary period, the hand-copies period, the Republican period, and the modern period.

Friday, October 10, 2014

The Spear in Japanese Martial Arts

There was a very good post about the Japanese spear, the Yari over at Ichijoji blog. An excerpt is below. The full post may be read here.

The spear is a weapon that has been used in some form in virtually every corner of the earth, and must be, after the club and the rock, one of the most basic weapons devised by mankind. Japan is no exception, and has a long tradition of the use of various pole arms, including spears, dating to way back before the 'samurai' era. However, as far as samurai are concerned, the spear was not even the principal pole arm until the 15th or 16th century. For some reason, it was the naginata that assumed that role, while the spear languished until the time of the Namboku-cho (1334-1392) when it gradually gained popularity. This popularity increased during the early Sengoku period, until, by the time of the famous warlords of the mid to late 16th century, it had assumed the position of one of the main weapons on the battlefield. This was partially due to logistical considerations, and indeed, the growing size of armies meant that it provided a cheap and easy to use armament for levies and other

irregular troops.

Though individuals became famous for their use of the spear, on the battlefield, their particular forte was in tactical deployment. Walter Dening, in his The Life of Toyotomi Hideyoshi, tells the story of how Hideyoshi got caught up in an argument to see whether long or short spears were superior. Oda Nobunaga's spear instructor favored short spears (short in this case means up to 8ft long) whereas Hideyoshi favored the longer type.

A trial was arranged: both men would train a group of fifty men in the use of their chosen length of spear,and after three days, the two groups would compete against each other. To cut a long story

short, while the spear instructor taught his men the techniques to oppose the longer weapons, Hideyoshi told his men they had the advantage anyway, so they could attack any way they liked, and wined and dined them. He also divided them into three units so they could make forward and flank attacks. On the day of the contest, Hideyoshi's men made mincemeat of his opponents.

Although this is probably an apocryphal tale, it does indicate the tactical value of the spear on the battlefield. That is not to deny that a shorter spear offers definite advantages to the individual warrior, but in battles employing formations of troops, longer spears offered a decided advantage. In fact, Nobunaga employed longer than average spears in his formations, and even on an individual level,

some warriors made use of the longer spears. Maeda Toshiie, for example, used one that was reportedly 6m in length.

The differences on such weapons also lead to certain specializations in the way they were used. For the ashigaru, who made up the bulk of the armies in the Sengoku period, spear usage was comparatively limited. Among the most common techniques was a downward strike aimed at knocking the opponent's spear downwards. This was particularly useful in tight formations, and contemporary writing suggests that this was seen as preferable to thrusting.

In fact, despite it's efficiency as a thrusting weapon, on the battlefield even the shorter spears were, as often as not, probably used to knock down an opponent and then despatch him. The triangular sectioned blade of the su yari (straight spear) was particularly effective for this, and this may also explain the popularity of the tanged spear head over the socketed type – the tang running deep inside the shaft gives greater durability as well as weighting the head, making it more effective for sweeping and striking movements.

Practice with long weapons quickly brings an appreciation of the difference in their range and speed compared with the sword. Facing someone with a spear (if they are using it well) allows one to realize the advantage it has – it is said that the spear gives its user a 3x advantage. When you see the speed with which a spear can be extended and retracted, how quickly the blade can shoot out at different targets, you appreciate how difficult it would be to face one in earnest.

The spear is a weapon that has been used in some form in virtually every corner of the earth, and must be, after the club and the rock, one of the most basic weapons devised by mankind. Japan is no exception, and has a long tradition of the use of various pole arms, including spears, dating to way back before the 'samurai' era. However, as far as samurai are concerned, the spear was not even the principal pole arm until the 15th or 16th century. For some reason, it was the naginata that assumed that role, while the spear languished until the time of the Namboku-cho (1334-1392) when it gradually gained popularity. This popularity increased during the early Sengoku period, until, by the time of the famous warlords of the mid to late 16th century, it had assumed the position of one of the main weapons on the battlefield. This was partially due to logistical considerations, and indeed, the growing size of armies meant that it provided a cheap and easy to use armament for levies and other

irregular troops.

Though individuals became famous for their use of the spear, on the battlefield, their particular forte was in tactical deployment. Walter Dening, in his The Life of Toyotomi Hideyoshi, tells the story of how Hideyoshi got caught up in an argument to see whether long or short spears were superior. Oda Nobunaga's spear instructor favored short spears (short in this case means up to 8ft long) whereas Hideyoshi favored the longer type.

A trial was arranged: both men would train a group of fifty men in the use of their chosen length of spear,and after three days, the two groups would compete against each other. To cut a long story

short, while the spear instructor taught his men the techniques to oppose the longer weapons, Hideyoshi told his men they had the advantage anyway, so they could attack any way they liked, and wined and dined them. He also divided them into three units so they could make forward and flank attacks. On the day of the contest, Hideyoshi's men made mincemeat of his opponents.

Although this is probably an apocryphal tale, it does indicate the tactical value of the spear on the battlefield. That is not to deny that a shorter spear offers definite advantages to the individual warrior, but in battles employing formations of troops, longer spears offered a decided advantage. In fact, Nobunaga employed longer than average spears in his formations, and even on an individual level,

some warriors made use of the longer spears. Maeda Toshiie, for example, used one that was reportedly 6m in length.

The differences on such weapons also lead to certain specializations in the way they were used. For the ashigaru, who made up the bulk of the armies in the Sengoku period, spear usage was comparatively limited. Among the most common techniques was a downward strike aimed at knocking the opponent's spear downwards. This was particularly useful in tight formations, and contemporary writing suggests that this was seen as preferable to thrusting.

In fact, despite it's efficiency as a thrusting weapon, on the battlefield even the shorter spears were, as often as not, probably used to knock down an opponent and then despatch him. The triangular sectioned blade of the su yari (straight spear) was particularly effective for this, and this may also explain the popularity of the tanged spear head over the socketed type – the tang running deep inside the shaft gives greater durability as well as weighting the head, making it more effective for sweeping and striking movements.

Practice with long weapons quickly brings an appreciation of the difference in their range and speed compared with the sword. Facing someone with a spear (if they are using it well) allows one to realize the advantage it has – it is said that the spear gives its user a 3x advantage. When you see the speed with which a spear can be extended and retracted, how quickly the blade can shoot out at different targets, you appreciate how difficult it would be to face one in earnest.

Tuesday, October 07, 2014

Saturday, October 04, 2014

The Key to Martial Arts Excellence: Showing Up

When I was a young man training in Aikido all of the time, there was an old guy (younger than me now) we called Wyandotte Joe, who was a brown belt.

He had never done anything athletic previously in his life and after a divorce, with his children grown and gone, had decided to take up Aikido.

He was limited in his range of motion (as I am now) and couldn't even sit in seiza (I can't anymore either). The movements didn't come easily to him (boy can I relate to that).

But he showed up every day. He was always there. He was undaunted in always trying to do his best.What an inspiration.

Below is an excerpt from an article I found at The Good Men Project. It was originally published at Six Pack Abs, where the full article may be read.

I sat in my car, looking out at the pouring rain. “Son of a bitch,” I said.

Warm and wet is fine. I’ve run in the rain in Maui and it was awesome. This was not going to be awesome. This was going to be cold and wet. In Canada, rain always sucks.

Stupid weather, messing with my workout plans.

I sat there in Rhonda the Honda, wasted some time on Facebook with my phone, and debated.

I needed to meet a friend downtown to pick up some tickets from him. Downtown traffic sucks.

Downtown parking fees are egregious. Parking 6K away from downtown, for free, then running to meet my friend and thereby avoiding the traffic, then running back, seemed like a great idea. I was dressed to run. I was ready to run.

But, rain. Crud.

I hate Canadian rain. I hated the thought of being cold and wet more than I hated the idea of traffic and parking fees.

Five minutes. I knew I could do five minutes. I also knew that going fast combated freezing. Suck it up, I said to myself. Just go for five minutes. If it’s horrible, turn back.

I ran the 6K in 27 minutes, a good pace, and walked into Starbucks. I was soaking wet and water was dripping from the brim of my hat.

“Holy shit, you ran here?” Dave said. Yeah, I guess I did. I hate forgotten about the miserable conditions within two minutes of hard running, and just did it. Grabbing a coffee the cute barista asked me the same question Dave had, minus the profanity, then, “What are you training for?” she asked.

“Life,” I said. I always wanted to say that. I managed to do it without sounding like a douche. She laughed, at least.

He had never done anything athletic previously in his life and after a divorce, with his children grown and gone, had decided to take up Aikido.

He was limited in his range of motion (as I am now) and couldn't even sit in seiza (I can't anymore either). The movements didn't come easily to him (boy can I relate to that).

But he showed up every day. He was always there. He was undaunted in always trying to do his best.What an inspiration.

Below is an excerpt from an article I found at The Good Men Project. It was originally published at Six Pack Abs, where the full article may be read.

I sat in my car, looking out at the pouring rain. “Son of a bitch,” I said.

Warm and wet is fine. I’ve run in the rain in Maui and it was awesome. This was not going to be awesome. This was going to be cold and wet. In Canada, rain always sucks.

Stupid weather, messing with my workout plans.

I sat there in Rhonda the Honda, wasted some time on Facebook with my phone, and debated.

I needed to meet a friend downtown to pick up some tickets from him. Downtown traffic sucks.

Downtown parking fees are egregious. Parking 6K away from downtown, for free, then running to meet my friend and thereby avoiding the traffic, then running back, seemed like a great idea. I was dressed to run. I was ready to run.

But, rain. Crud.

I hate Canadian rain. I hated the thought of being cold and wet more than I hated the idea of traffic and parking fees.

Five minutes. I knew I could do five minutes. I also knew that going fast combated freezing. Suck it up, I said to myself. Just go for five minutes. If it’s horrible, turn back.

I ran the 6K in 27 minutes, a good pace, and walked into Starbucks. I was soaking wet and water was dripping from the brim of my hat.

“Holy shit, you ran here?” Dave said. Yeah, I guess I did. I hate forgotten about the miserable conditions within two minutes of hard running, and just did it. Grabbing a coffee the cute barista asked me the same question Dave had, minus the profanity, then, “What are you training for?” she asked.

“Life,” I said. I always wanted to say that. I managed to do it without sounding like a douche. She laughed, at least.

Wednesday, October 01, 2014

The Brilliance of the Chinese Longsword

We have another guest post by Jonathon Bluestein. The topic of this one is the Chinese Longsword. Enjoy.

The Brilliance of the Chinese Longsword

The

purpose of this very long article is to familiarize readers with a uniquely

Chinese weapon – the Miao Dao. During the 20th century, this sword

has been pushed out the spotlight in favour of the much more popular Dao (Broadsword),

Da Dao (Huge Broadsword), Guan Dao (a staff with a huge broadsword blade at its

end), and the Jian (the Chinese straight, double-edged sword).

Historically-speaking however, the Miao Dao was very popular on the Chinese

battlefields, and nowadays it is regaining its popularity in various martial

arts communities in China, south-east Asia and the West alike. The article

shall first discuss the history of the sword, later its structure and utility,

and at last its training methods, usage in the martial arts and the

characteristics of it in fighting.

In the picture: the author, shifu Bluestein, wielding a typical modern training miao dao. This is a generic model that was very common in China throughout the early 21st century.

The weapon’s history and name

Two-handed swords of various styles have a history in China which goes back over 2000 years. According to my teacher, late master Zhou Jingxuan, the first Miao Dao date back to about the 5th century. It emerged around the time when round hilt guards first became widespread in Chinese sword design. It was known by many names throughout history. Originally it was mostly commonly referred to as simply ‘Chang Dao’ (長刀; Longsword). Later in the Ming and Qing dynasties (1368-1644 AD, 1644-1911 AD), it was plainly called ‘two-handed sword’. At that time, it was also commonly known as ‘Mao Dao’ (矛刀; Spear-sword). Another name for it over the centuries (beginning in the Song dynasty, 960 – 1279 AD) had been ‘Zhan Ma Dao’ (斩马刀) – Horse Cutting Sword. An appropriate name for a blade which is big, heavy and fearsome enough to cut down horses’ legs and stab them to death. This may sound archaic, but modern Miao Dao forms still feature movements which can be used for such horrendous purposes, and the weapon can be demonstrated to easily cut through the corpses of large animals (this I saw myself on Chinese documentaries, even when the cutting swords were held by only moderately-skilled individuals). The sword was also wielded by cavalrymen, and when used in that fashion it was most often utilized for stabbing (rather than hacking, cutting or slashing). Since all of these names were used interchangeably, sometimes they referred to miao dao, and other times to very similar designs with some modifications.

The modern name, ‘Miao Dao’ means ‘Sprout Sword’, and refers to the resemblance of a grounded sword (blade in ground and handle facing upwards) to that of some green sprouts. My teacher told me that the reason the sword began to be referred to by this name was confusion in pronunciation, with ‘Miao Dao’ sounding similar to ‘Mao Dao’. This error persisted and the name stuck.

In the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644 AD) there

had lived a very famous martial artist – General Qi Jiguang (November 12, 1528 – January 5,

1588). Born into a hereditary military family, he came to hold a mythical

position in Chinese military history and culture. During his lifetime and

career, the Chinese army was busy fighting off Japanese pirates, and it is more

than likely that at the time, Miao Dao and Katanas crossed blades on the

battlefield. Indeed, in the 14th century painting below, dated

before the time of Cheng Chongdou and Qi Jiguang, we already see Japanese pirates (Wokou 倭寇)

wielding what appears to be Katanas (this is also evident in other paintings of

these pirates), and it is known that many of them were former Samurai (those

who wish to read more about these pirates can do so here: http://www.nippon.com/en/features/c00101/ ). Qi was called forth to command the

resistance against these pirates, who were attacking the cities of Zhejiang

province (浙江省), which he eventually did quite successfully, partly by utilizing

the miao dao as counter-measures to the very long nodachi used by the pirates.

In the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644 AD) there

had lived a very famous martial artist – General Qi Jiguang (November 12, 1528 – January 5,

1588). Born into a hereditary military family, he came to hold a mythical

position in Chinese military history and culture. During his lifetime and

career, the Chinese army was busy fighting off Japanese pirates, and it is more

than likely that at the time, Miao Dao and Katanas crossed blades on the

battlefield. Indeed, in the 14th century painting below, dated

before the time of Cheng Chongdou and Qi Jiguang, we already see Japanese pirates (Wokou 倭寇)

wielding what appears to be Katanas (this is also evident in other paintings of

these pirates), and it is known that many of them were former Samurai (those

who wish to read more about these pirates can do so here: http://www.nippon.com/en/features/c00101/ ). Qi was called forth to command the

resistance against these pirates, who were attacking the cities of Zhejiang

province (浙江省), which he eventually did quite successfully, partly by utilizing

the miao dao as counter-measures to the very long nodachi used by the pirates.

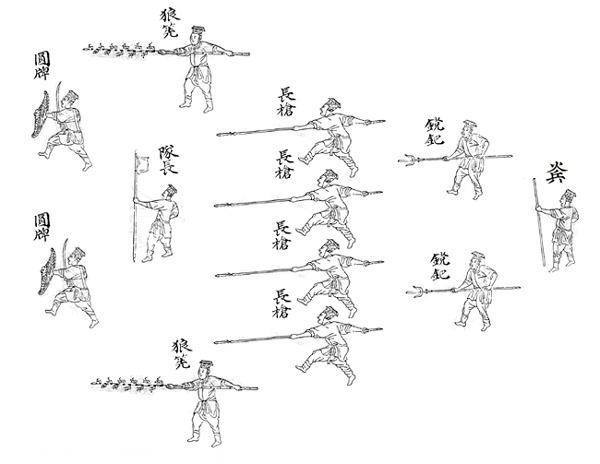

Initially, in 1557, Qi trained 3000 volunteers to fight the pirates. The fighting went badly for them in the following year, and Qi reasoned that one of the chief reasons was that the majority of these soldiers were urban dwellers, who did not possess strong physical foundation for fighting. Henceforth, Qi decided to only train farm boys for the job. He further honed his strategies by inventing the ‘Mandarin Duck Formation’. This squad was composed of basic units of twelve men each, consisting of two rattan shield & sword men, one leader (carrying a flag), two with bamboo lances, and four with long lances, two fork (trident) men, and a cook, who also acted as a logistics man. They were to advance in that order, or in two five man columns dividing the weapons equally, but with the strict ruling that all acted to protect the leader from being wounded. Had the leader lost his life, during a battle that ended in defeat, any survivor in his unit was to be executed. Thus each man was drilled in the spirit of win or die. At the same time the weapons were specifically designed to fight the Pirates whose long bows were deadly and whose sharp swords could sever any Chinese hand weapon. In Qi’s tactics the shield was to take care of the arrows, and the bamboo lance, with its bushy branches intact, could slow down the onslaught and entangle the swordsman making it possible for the other lancers to dispatch him. The lengthened blades of the swords also accommodated for the long Japanese reach. The image above, illustrating the Mandarin Duck Formation, was taken from General Qi’s book military tactics which he wrote following the successful anti-pirate campaigns, in 1560 (age 32). The book was called ‘Quanjing Jieyao Pian’ – A New Treatise on Disciplined Service. Free English translations of this book are available online.

General

Qi Jiguang also famously issued Miao Dao swords to many of his soldiers when

fighting the Mongols. Qi was only 22 years old (1550) when the Mongols breached

through the walls of Beijing, and he helped defend the city. In the aftermath,

he and others proposed taking the fight with the Mongols to the northern

borders, to prevent such an event from recurring. The Mongol front was far from

that Qi Jiguang had with the Japan, which serves to demonstrate the sword had

proven much versatility in usage under different conditions and upon various

terrains.

Qi served protecting the Great Northern Wall from Mongol threats in the years 1568-1583. He repaired the Wall, built more observation towers (to serve as his early warning net), organized training centers, and concentrated on drilling cavalry and wagon troops. He thought that the Mongols, like the pirates, were strongest in their element: in their case, on horseback on hard ground. His defense strategy emphasized attacking the Mongols once they had either penetrated, or been allowed to penetrate, the Great Wall. Miao Dao were were issued to four types of squads: Combat Wagon squads who used their wagons as cover, Baggage Supply Wagon squads, regular infantry squad which was similar to the Mandatin Duck Formation, and a Cavalry squad. Each of these had men wielding miao dao, which were at the time called ‘Chang Dao’ (Longsword). Usuaully, they were carried by bowmen and musketeers, to be used after the ammunition was exhausted.

Qi served protecting the Great Northern Wall from Mongol threats in the years 1568-1583. He repaired the Wall, built more observation towers (to serve as his early warning net), organized training centers, and concentrated on drilling cavalry and wagon troops. He thought that the Mongols, like the pirates, were strongest in their element: in their case, on horseback on hard ground. His defense strategy emphasized attacking the Mongols once they had either penetrated, or been allowed to penetrate, the Great Wall. Miao Dao were were issued to four types of squads: Combat Wagon squads who used their wagons as cover, Baggage Supply Wagon squads, regular infantry squad which was similar to the Mandatin Duck Formation, and a Cavalry squad. Each of these had men wielding miao dao, which were at the time called ‘Chang Dao’ (Longsword). Usuaully, they were carried by bowmen and musketeers, to be used after the ammunition was exhausted.

Later

in his life, Qi Jiguang wrote another book, about the Miao Dao, titled ‘Xīn Yǒu

Dāo Fǎ’ (辛酉刀法).

The words ‘Xīn Yǒu’ refer to the year the book was released in during the Ming

dynasty (58th year of a 60 year cycle), and ‘Dāo Fǎ’ means ‘Sword

Methods’. Together – ‘The Sword Methods of the 58th Year’.

The

weapons of General Qi Jiguang’s soldiers and their opponents also tell us much

about how skilled these men were. It is written and recorded in both Japanese

and Chinese histories that during that era, the Samurai, Japanese Pirates and

General Qi’s soldiers commonly used swords that reached the upwards of 200cm in

length. A true battlefield miao dao at the length of 135cm, such a sword I own

myself, weighs roughly 2.5kg. This means a miao dao or nodachi as long as 200cm

should weigh over 3.5kg. Let it make this very clear – such a weapon is

unwieldy for normal individuals in our time, even most well-trained martial

artists. To be able to effectively fight with a sword so massive and

effectively control it for many minutes, perhaps hours on end in combat, means

that the Asian warriors of the period were exceptionally fit and strong. Each

must have been an equivalent in ability to a superior, world-class athlete of

our time.

In the pictures: Left - A samurai of that era, with a huge nodachi, which I estimate to be about 2 meters long. Note that the mass and lever of this massive weapon are further added to by the armor this warrior had to carry!

Right – Manchurian soldiers from the 1640s (a generation after Qi Jiguang’s death), carrying Miao Dao. Based on the ratio of weapon-to-body seen in this painting, I estimate the length of the swords to be 135-155cm – about the same as modern miao dao.

Much time had passed since the days of Qi Jiguang, and the Miao Dao was nearly forgotten. Its place was taken by the classic broader, shorter and more curved design of the Dao. Cold weapons were in any case undergoing a long process of being permanently replaced by firearms. Despite this, various miao dao traditions persisted, scattered across China.

A little later, but at around the same

period (of Qi Jiguang) had lived another famous martial artist by the name of Cheng Chongdou (程冲斗 ;

Also known as Cheng Zongyou 程宗猷). He was born around 1561 in Anhui province. He is said

to have been called by a representative of the Chinese emperor to teach army

troops in Tianjin when he was 62 years of age. Skilled with many weapons, he

wrote a famous book about the usage of Miao Dao, titled ‘Dān Dāo Fǎ Xuǎn’ (单刀法选)

– ‘Selected (most important) Techniques of the Single Sword’. In the book are

also notably featured other weapons, such as a crossbow (being carried by the

soldiers as he wields the Miao Dao) and a short dagger (which is depicted as been carried passively or thrown at an

opponent). The image to the left is from his book.

A little later, but at around the same

period (of Qi Jiguang) had lived another famous martial artist by the name of Cheng Chongdou (程冲斗 ;

Also known as Cheng Zongyou 程宗猷). He was born around 1561 in Anhui province. He is said

to have been called by a representative of the Chinese emperor to teach army

troops in Tianjin when he was 62 years of age. Skilled with many weapons, he

wrote a famous book about the usage of Miao Dao, titled ‘Dān Dāo Fǎ Xuǎn’ (单刀法选)

– ‘Selected (most important) Techniques of the Single Sword’. In the book are

also notably featured other weapons, such as a crossbow (being carried by the

soldiers as he wields the Miao Dao) and a short dagger (which is depicted as been carried passively or thrown at an

opponent). The image to the left is from his book.

In the picture:

An image from Cheng Chongdou’s book, Dān Dāo Fǎ Xuǎn. The book features

a lot of illustrations of soldiers carrying crossbows, together or without a

Miao Dao. As seen here, the crossbow (like the musket) took a whole-body effort

and quite a lot of time to load, and could not have been used together with the

Miao Dao. At the time, a popular tactic would have been to utilize projectile

weaponry from a safe position or shelter, and resort to an all-out charge at

the enemy once ammunition ran out. It is interesting that in this book, the

soldiers are often both archers and infantrymen, while in European Medieval

armies there would have been a greater distinction between the two fighting

classes. It seems that the crossbow, being easier to shoot with than the bow,

allowed for more verasatility in its uses among the soldiers.

In

the beginning of the 20th century, master Guo Chengsheng (1866-1967)

combined his extensive knowledge of Pigua Zhang (a Chinese martial art) with

that he had of the Miao Dao, and created a second variation for the Miao Dao

form (known as ‘Er Lu’ – Second Road), with the aid of his friend, master Ma

Yingtu. Both the first (original) and second form are mostly closely associated

with the techniques shown in Cheng Chongdou’s book, Dān Dāo Fǎ Xuǎn. Here is a

video of my teacher, master Zhou Jingxuan, performing the Er Lu Miao Dao form:

As of now, I am aware of at least

four distinct miao dao traditions still extant in China:

1.

Master Han Yiling of Hebei province created a comprehensive martial arts style

which he named ‘Cloud Demon’, and taught in the late 20th and early

21st centuries. The curriculum included the practice of miao dao,

which Han possibly learned in Tianjin from his Tongbei teacher, Deng Hongzao.

2.

A lineage passed down within the Hui Muslim community of Xin Yi Liu He’s miao

dao. In the 20th century it was passed down by Liu Fengming and his

disciple Song Guobin, and notable masters of it who were likely still living in

the early 2000s were Ma Zhiqiang (马志强) and Liang Hong Xuan (from Bengbu, Anhui province). There

appear to be at least two long forms in this lineage. Routine one has 58

postures, and routine two has 64 postures. The tradition is called Wansheng

Miao Dao after the Wansheng Security Firm. The Wansheng company, which

provided armed escort services, adopted this sword somewhere between the end of

the Ming dynasty and the beginning of the Qing dynasty and made it a specialty

weapon of theirs. The miao dao were originally up to five chi, or 166cm long

(blade 126cm and handle 39cm), with the weight of 2.5kg. This tradition now

have a fixed length of 150cm (handle 20c, blade 130cm) and weigh 1.25kg.

Unique, the practitioner will also perform with a set of three throwing knives

attached to waist, which would be tossed in the middle of a form (the knives

resemble the Japanese Kunai). This method was also featured in the Qi Jiguang’s

book, Xīn Yǒu Dāo Fǎ.

3.

The Guo Changsheng lineage, to which I belong: Cheng Chongdou, Qi Jiguang and others in

ancient times >>>>>>>>>>>>>> Mr. Yang (18th century) >>> Xie

Jinfen (18-19th centuries) >>> Liu Yuchun (19th century; instructor at

the Nanking Central Martial Arts Academy. Was a master of Pigua, Tongbei and

Miao Dao) >>> Guo Chengsheng (1866-1967) >>> Guo Fengming >>> Pang Zhiqi &

Wang Lianhe (20th century) >>> Zhou Jingxuan (in the video

above) >>>  Jonathan Bluestein. | Though

Guo Changsheng’s teachings of the Miao Dao had been of traditional

battlefield techniques, over time his forms spread across China, with the

majority of people practicing them in altered versions, adhering to the mindset

and framework of modern sports Wushu. Thus, it came to be that as in the past,

relatively few people still practice the Miao Dao as originally intended. In

our lineage, the length of the Miao Dao changes according to the person’s

height, and the weight according to personal preference and ability. The handle

should be the length that is measured between the end of one’s elbow and the

end of one’s one’s outstretched pinky finger, on the same arm.

Jonathan Bluestein. | Though

Guo Changsheng’s teachings of the Miao Dao had been of traditional

battlefield techniques, over time his forms spread across China, with the

majority of people practicing them in altered versions, adhering to the mindset

and framework of modern sports Wushu. Thus, it came to be that as in the past,

relatively few people still practice the Miao Dao as originally intended. In

our lineage, the length of the Miao Dao changes according to the person’s

height, and the weight according to personal preference and ability. The handle

should be the length that is measured between the end of one’s elbow and the

end of one’s one’s outstretched pinky finger, on the same arm.

Jonathan Bluestein. | Though

Guo Changsheng’s teachings of the Miao Dao had been of traditional

battlefield techniques, over time his forms spread across China, with the

majority of people practicing them in altered versions, adhering to the mindset

and framework of modern sports Wushu. Thus, it came to be that as in the past,

relatively few people still practice the Miao Dao as originally intended. In

our lineage, the length of the Miao Dao changes according to the person’s

height, and the weight according to personal preference and ability. The handle

should be the length that is measured between the end of one’s elbow and the

end of one’s one’s outstretched pinky finger, on the same arm.

Jonathan Bluestein. | Though

Guo Changsheng’s teachings of the Miao Dao had been of traditional

battlefield techniques, over time his forms spread across China, with the

majority of people practicing them in altered versions, adhering to the mindset

and framework of modern sports Wushu. Thus, it came to be that as in the past,

relatively few people still practice the Miao Dao as originally intended. In

our lineage, the length of the Miao Dao changes according to the person’s

height, and the weight according to personal preference and ability. The handle

should be the length that is measured between the end of one’s elbow and the

end of one’s one’s outstretched pinky finger, on the same arm.

In the picture:

Guo Changsheng’s son, Guo Ruixiang (born 1932), himself a famous master.

Note the closeness of the blade to the thigh as it passes in a circular fashion

near it – a trademark of Miao Dao movements.

The Guo family still manufactures and sells their own Miao Dao: http://www.guoruixiang.com/wangshang_jpzs.htm

The Guo family still manufactures and sells their own Miao Dao: http://www.guoruixiang.com/wangshang_jpzs.htm

4.

There might exist in Korea a fourth school, or several schools, of miao dao. A

sword the size of the miao dao with an odachi-like design, called ‘Ssang Su Do’

(Double-Handed Saber), is featured in a few Korean traditions. It has been

suggested that when the Chinese Ming Dynasty troops lent their assistance to

Korea against the Japanese invasion, General Qi Jiguang's sword methods were

taught to the Koreans. These were later adapted and included in the comprehensive

Korean martial arts manual, ‘Muye Dobo Tongji’, under the Ssang Su Do chapter.

Physical appearance and design

The sword which bears the greatest similarity to the Miao Dao in design is strangely the Japanese Katana. This must be an uncomfortable piece of truth for the Chinese and Japanese, a large percentage of whom had been seriously resenting each-other (for good reasons) over the last few centuries. General Qi Jiguang even had the miao dao of hi soldiers made like traditional high-quality Japanese katanas – with laminated construction, creating a hard steel edge and more flexible iron spine.

Some claim that the Miao Dao is the sword that inspired the creation of the Japanese Katana. This sounds reasonable given the fact that Japan had borrowed significant portions of its culture, art, philosophies and even its entire writing system from China. However, Katanas are evidenced to have existed in Japan already countless generations ago – from at least the 14th century (The abovementioned Ming Dynasty in which the Miao Dao became commonplace, was only established in 1364). This puts into question the former claim of native Chinese influence, and it is possible that there had been cross-influences in the development of both swords. Nonetheless, it is still claimed by some that the Miao Dao influenced the creation of the Katanas before that time, perhaps even as early as the Tang Dynasty (618–907 AD).

I

have also encountered claims that Cheng Chongdou, author of the Miao Dao book

Dān Dāo Fǎ Xuǎn I mentioned earlier, was influenced by the Samurai school

called Shin Kage Ryu (新陰流; ‘New Shadow School’), and that Qi

Jiguang, author of the other Miao Dao book, Xīn Yǒu Dāo Fǎ, based his work upon

a Japanese swordsmanship manual he acquired in battle. We cannot tell how much

of this is true. In modern times, the body mechanics of traditional Koryu

styles are extremely different to Chinese Miao Dao methods. Furthermore, the

Katanas had always been shorter than the Miao Dao, and the substantial

difference in both length and weight, as well as handle size, etc, makes for a

very different wielding experience. Such things would be compared more thoroughly

later in the article.

Another important point to consider is that Shin Kage Ryu was founded in the middle of the 16th century (when Qi Jiguang was already middle-aged and Cheng Chongdou was a child). This means that for this styles to have influenced any of the two, it ought to have become very influential and widespread within less than 30-40 years – so wide spread as to reach the shores of a different continent, wherein it would be used by several people and influence two major military figures in a foreign army. While possible, this is unlikely. To add to this unlikelihood, Qi Jiguang’s book is said to have been written circa (1560) – around the time Shin Kage Ryu was founded, and at most not long afterwards. The comparisons drawn with Shin Kage Ryu seem to have been based on matching supposed similarities between written manuals, which is often a poor way to make such judgments, especially when the persons involved are self-taught on the art of sword wielding.

Another important point to consider is that Shin Kage Ryu was founded in the middle of the 16th century (when Qi Jiguang was already middle-aged and Cheng Chongdou was a child). This means that for this styles to have influenced any of the two, it ought to have become very influential and widespread within less than 30-40 years – so wide spread as to reach the shores of a different continent, wherein it would be used by several people and influence two major military figures in a foreign army. While possible, this is unlikely. To add to this unlikelihood, Qi Jiguang’s book is said to have been written circa (1560) – around the time Shin Kage Ryu was founded, and at most not long afterwards. The comparisons drawn with Shin Kage Ryu seem to have been based on matching supposed similarities between written manuals, which is often a poor way to make such judgments, especially when the persons involved are self-taught on the art of sword wielding.

I

was told, in confidence by a martial arts historian whom I trust, that there is

in existence a decent and authentic Japanese drawing of a very (!)

notable Japanese samurai, a founder of a known system, wearing Chinese armor of

his period. This would be a very clear proof that Samurai warfare was

influenced by Chinese methods. Unfortunately, I was sworn to refrain from

revealing, in public or private, who is the person in question and what

was his style, because this information has been handed out in trust and

secrecy. Other records of Chinese influence over Japanese swords arts also

exist (http://www.kashima-shinryu.jp/English/i_history.html).

We know for instance that Ogasawara Genshinsai (1574–1644), the 4th

inheritor of Shin Kage Ryu, lived for a period in Beijing, China, where he

studied Chinese fist and weapons methods and also taught Japanese Bujutusu to

the Chinese (this is documented, based on translations from ancient scrolls, in

a book called ‘Legacies of the Sword: The Kashima-Shinryū and Samurai Martial

Culture’).

In

terms of metalworking, it is important to remember that Japan, unlike China,

had always been scarce in natural resources, and especially high quality steel.

This had forced Japanese swordsmiths to become more innovative in their art,

and also significantly prolonged the time it took them to produce blades. These

facts made the Katana a very prized weapon – the weapon of professional

warriors (Samurai) and the aristocracy. Blades like the Miao Dao, on the other

hand, could have been more readily made in China, and their commonality made

them less valuable – financially, culturally, artistically and otherwise.

The entire cultural perception of these weapons varies significantly. This would soon be illustrated when comparing their innate structural attributes and physical form, but can already be witnessed by a keen eye in the pictures presented so far in the article. For instance - above in the first image in this article, we see a soldier throwing the sword in the air and catching it (a technique still found in the Wansheng tradition). This type of action is unheard of in Japanese Koryu arts as they are practiced today. Not to mention the fact that Miao Dao forms utilize classic stances from Chinese gong fu – Ma Bu, Gong Bu, Hou Bu, etc – which are not identical to those used in Japanese arts. With regard to the significance of the sword to its owner – the Japanese Samurai often considered the words to be ‘his soul’, and would bow to it before practice. That type of near-religious practice is not something a Chinese warrior would do. At least, it is not something the Chinese have kept in practice into modern times.

The entire cultural perception of these weapons varies significantly. This would soon be illustrated when comparing their innate structural attributes and physical form, but can already be witnessed by a keen eye in the pictures presented so far in the article. For instance - above in the first image in this article, we see a soldier throwing the sword in the air and catching it (a technique still found in the Wansheng tradition). This type of action is unheard of in Japanese Koryu arts as they are practiced today. Not to mention the fact that Miao Dao forms utilize classic stances from Chinese gong fu – Ma Bu, Gong Bu, Hou Bu, etc – which are not identical to those used in Japanese arts. With regard to the significance of the sword to its owner – the Japanese Samurai often considered the words to be ‘his soul’, and would bow to it before practice. That type of near-religious practice is not something a Chinese warrior would do. At least, it is not something the Chinese have kept in practice into modern times.

In the

pictures: Above - an image from Cheng Chongdou’s book,

Dān Dāo Fǎ Xuǎn. Below – two 20th century practitioners of Ninjutsu,

of the Bujinkan school, help each other draw their Nodachi.

Historical

documents teach us that Miao Dao were always fairly long – so long at times,

that some varieties could not have been unsheathed single-handedly with ease

when the scabbard is attached to the body, and to speed the process bearers

would be aided in this action by their partner before or during combat. We see

this in the picture above (though ironically, the swords featured in the image

are in fact easily sheathable by a single person). At a greater length this

would make sense, as the swords would be too long to be carried at the waist,

and would have to be positioned on one’s back. At that position, having a

friend to do the drawing for your saves a lot of time. This was also common

practice with Japanese Odachi. Another solution for quick drawing had been to

grab the handle and throw the sword directly upwards into the air, catching it

as soon as it fully exists the scabbard and lowers to the ground. This method

is recorded in the practice of the Wansheng tradition.

Though Miao Dao lengths can vary greatly, one constant has been that they are always notably longer than most Japanese Katanas, and therefore not suitable for quick drawing and with a tendency for clumsiness at indoor fighting. Unlike the Chinese straight sword (Jian), these swords were not originally intended for dueling – they were first and foremost instruments war. This is important to remember for another reason. The Miao Dao’s greatest enemies on the battlefield were not other Miao Dao, but spears and staffs (AKA cut-off spears), because they had a significantly longer reach. The Miao Dao has the edge to cut through these weapons (and even harder objects), but that requires timing, skill and very specific angles. I shall go more into these things as the article progresses.

Though Miao Dao lengths can vary greatly, one constant has been that they are always notably longer than most Japanese Katanas, and therefore not suitable for quick drawing and with a tendency for clumsiness at indoor fighting. Unlike the Chinese straight sword (Jian), these swords were not originally intended for dueling – they were first and foremost instruments war. This is important to remember for another reason. The Miao Dao’s greatest enemies on the battlefield were not other Miao Dao, but spears and staffs (AKA cut-off spears), because they had a significantly longer reach. The Miao Dao has the edge to cut through these weapons (and even harder objects), but that requires timing, skill and very specific angles. I shall go more into these things as the article progresses.

The

length of the Miao Dao used in my lineage varies proportionally to the height

and measurements of the practitioner. The handle should be anywhere between the

length of one’s forearm and fist put together, and the distance between one’s

elbow and the edge of the pinky finger. That is pretty long compared with a

Katana’s handle, and has several purposes. First and most important, to make it

easier to switch hand positions. Second, so a wider grip could be used – making

for a more effective lever, and allowing for arms and shoulders to open more in

movement (this is important for utilizing the structural mechanics of wielding

a Miao Dao in the Pigua style). Interestingly, because the length of the handle

reflects that of a person’s forearm and palm, and the grip slides along and

changes all the time, training with the Miao Dao also coincidentally aids in

learning to work with an opponent’s arm when empty-handed, teaching a certain type

of sensitivity in this regard.

The height of the blade reflects utility of action. A characteristic Miao Dao technique which we use involves an upwards slashing with the sword, following the drawing of a large circle. To increase effectiveness and partially hide the sword from the opponent’s field of vision, the sword’s circle is drawn as close to one’s body as possible, passing very near to one’s legs (the unskilled can actually cut themselves). Given that the blade is in this sort of action almost perpendicular to the ground in the moment before the upward slashing maneuver, it ought to be short enough to avoid hitting the ground, yet long enough to maximize potential reach. For a person of modest height such as myself, at 170cm (5’7) tall this makes the length of Miao Dao most appropriate for me about 135cm (4’4). Another member of your gongfu family, Etai, is about 196cm (6’4) tall, and his Miao Dao is proportionally longer. Still, at the more common length of about 135cm (4’4), the Miao Dao is fairly close to the upper-end of longer Medieval Broadswords (~130cm) and is comparable with the length of traditional Claymores (120-140cm), while being smaller than most Greatswords (130-180cm). Interestingly, the miao dao and these European swords I just mentioned rose to prominence at about the same time frame in history, during the 15th century. Note that unlike their mistakenly stereotyped image, the ‘Chinese’ are not necessarily a short people at all (and

respectively, their swords are not necessarily small!). Up north in Tianjin

city where my teacher resides, many males exceed the height of 182cm (6’), and

northwards to Tianjin people can be even bigger.

necessarily a short people at all (and

respectively, their swords are not necessarily small!). Up north in Tianjin

city where my teacher resides, many males exceed the height of 182cm (6’), and

northwards to Tianjin people can be even bigger.

The length of the Miao Dao, though suggested as limiting at times in close quarters within walls, has of course the advantage of reach, and the latter is not limited to offense. With a shorter sword, when another weapon is aimed at one’s lower extremities, one is often forced to crouched in order to parry, or jump to avoid being hit or cut (as common in Katori Shinto Ryu). The Miao Dao is long enough to defend these parts without resorting to such methods, and the body can be used for other purposes instead (though forward leaping, as opposed to jumping in place, does exist in the practice of this sword).